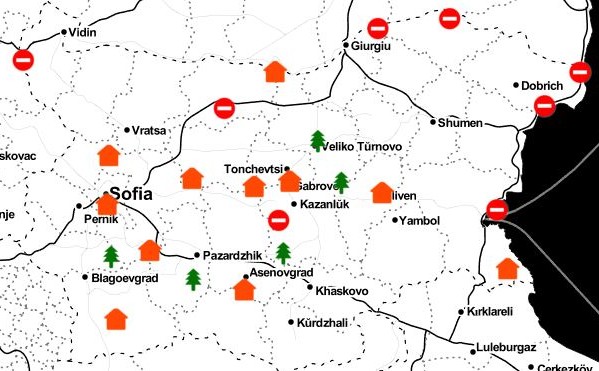

tl;dr I made a map that shows all Bulgarian OpenStreetMap buildings that sit within Bulgarian nature areas.

Bulgaria is a beautiful country brimful with amazing nature: it has great mountains to hike, expansive plains with cute villages and cosy towns to visit and a beautiful Black Sea coast fit for relaxing in the sun.

I’ve seen a fair share of Bulgaria’s natural beauties. We grew up in the capital Sofia and climbed the nearby Vitosha mountain regularly. In the last couple of years we hiked across the major mountains Rila, Pirin, The Balkan and Rhodope Last year we switched the hiking boots for wheels and cycled along the south coast and into the beautiful Strandzha region.

All this beauty is, sadly, under constant threat of being built on. At first you are oblivious to this threat; you see a luxurious mansion on a beautiful spot high in the mountain and are envious of the lucky owner.

This thin veneer quickly comes off after you start talking to the locals. They often tell of unruly property owners who build wherever they want, even in nature reserves that forbid construction. Suddenly that new hotel isn’t so inviting anymore. The most recent case in point is a recently approved 50 million project near Karadere on the Black Sea coast.

With each new story, a desire to get an overview of the situation solidified into a need for a picture of all buildings in the Bulgarian nature reserves.

Being a geo geek I made a map of the Bulgarian nature reserves and the buildings located therein. The map shows information from OpenStreetMap (OSM) and the Bulgarian Executive Environment Agency on top of Google’s satellite imagery.

In addition to creating an overview, the application invites people to contribute information through OSM’s interface as an experiment in crowdsourced monitoring.

Obtaining data

Finding the Bulgarian buildings proved the biggest challenge as only 18% have been mapped by the Bulgarian cadaster. On top of that, the data is closed and paywalled.

National cadasters nowadays have worthy competition from the crowdsourced effort OpenStreetMap. OSM is a Wikipedia for geographical information: anyone can sign up and start mapping the world around them by drawing points, lines and polygons on a map that represent trees, hiking trails, buildings, etc. An object’s property is described by tags consisting of key/value pairs e.g. a building’s entrance is mapped by placing a point on the map and tagging it with entrance=yes. An OSM object can theoretically have an infinite number of properties. OSM thus contains millions upon millions of richly described objects.

Downloading information from OSM is, thanks its awesome community, a piece of cake: OSM developers have built a myriad of powerful tools, such as overpass turbo, that let you query and download OSM data. For this map I downloaded all buildings that fit in Bulgaria’s bounding box (see the github repository for more information.

The second piece of information we need is the location and extent of Bulgarian nature areas. This information is readily available from Bulgarian Executive Environment Agency in a convenient geo format.

Lastly, we need the Bulgarian nature reserves law in order to determine where construction is and isn’t allowed in order to classify the buildings accordingly.

Painting the picture

In the end I’m only interested in buildings that sit within nature areas. These are easily filtered from all Bulgarian OSM buildings we obtained earlier by intersecting them with the nature areas and keeping only those that are located within a reserve. Each building is then classified according to its tourism key value and the type of area it sits in. Buildings with an empty tourism property are classified as non-touristic. This results in the following classes:

- suspicious: non-tourist buildings that are located in nature areas in which construction is forbidden

- unknown: non-tourist buildings that are located in nature areas in which construction is not forbidden

- valid: tourist buildings i.e. buildings whose tourism value is alpine_hut, attraction, camp_site, etc.

The map shows these as red, orange and green, respectively.

Usage and user engagement

The primary goal of the map is to shine a light on the situation: where are the protected areas, how many buildings do they contain, where are these located, what is their type, etc.

A secondary goal, and for me a much more exciting one, is to experiment with crowdsourcing. As stated above, the “open” in OpenStreetMap means that anyone can log in and modify/enrich the information. Adding information to OSM is easy; there are a myriad of mapping online/offline editors with varying degrees of functionality. People’s contribution can range from adding a single building property (e.g. adding a tourism=yes property to a suspicious building so it turns green), to adding a missing label, mapping new buildings, etc. Once the information hits OSM, it’s fairly straightforward to automate the download and intersection process described above so that changes made in OSM automatically propagate to the map. OSM thus becomes a crowdsourced monitoring platform.

The question is, of course, are people willing to contribute?

Finally, my third goal (or rather, hope) is that the application will draw new mappers to OpenStreetMaps who, after adding/fixing the information relevant for this map, will “spill over” to other locations and types of information and start mapping their neighbourhood, town, favourite hiking spot, etc. thereby enriching the Bulgarian OSM as a whole.

Shortcomings

This process and resulting map has a number of shortcomings. For one, OpenStreetMap is not complete; some buildings are missing descriptive information while others are absent altogether. Some buildings are therefore falsely labelled as being “suspicious” while other are missing from the map. Luckily these “issues” are easy to fix by anyone by simply logging into OSM and editing the data.

A semi-technical question is what will happen if someone does not want a certain property to be mapped? Just as anyone is free to add information, removing a property is as easy.

There are also non-technical weaknesses. It is for instance not clear what was there first: the buildings or the protected area? The map is furthermore dangerous as it easily makes false accusations; a suspicious building may not be in violation even though it is not tagged touristic e.g. power stations, military buildings, buildings with permits/exceptions. These types of shortcomings are harder to solve as they require access to legal documents such as building permits. Getting these will not be easy as it mostly involves footwork.

The map must therefore not be seen as a definite answer but a mere instrument for discussion and an exploration of thematic crowdsourced monitoring. A lot of work is still required before it becomes a tool for action.

Next steps

The wonderful people at Obshtestvo.bg are interested in the idea and are offering support (and encouragement 🙂 ) which I’ll gladly accept in due time. First I want to polish the map (by implementing filters, address lookup, etc.) and study the regulations more thoroughly.

Once that’s done, I’ll send the map to Bulgarian nature preservation organisations to see whether they find the idea and application useful.